Many humanities-inflected attempts to understand large language models (LLMs), and other kinds of machine learning, gathered under the name of Artificial Intelligence, seem to begin their investigations in the early modern period. John Haugeland’s extremely useful primer, Artificial Intelligence, The Very Idea, for example, begins by twining early modern European philosophy of mind and of science together. As modern scientific theories about the nature of the universe were emerging—the copernican revolution— we needed a new picture of how the mind worked. The language of the universe, it turned out was mathematics, so was mathematics also the language of the mind? Thomas Hobbes thought so:

By Ratiocination, I mean Computation…

When a man reasoneth, he does nothing else but conceive a sum total, from addition of parcels; or conceive a remainder, from subtraction of one sum from another.... These operations are not incident to numbers only, but to all manner of things that can be added together, and taken one out of another.

We see there, in embryonic form, a struggle to define the mind in relation to mechanism. Is the mind a machine or not? This is the question modern cognitive science still wants to answer.

In this sense, LLMS are boundlessly philosophically fascinating. The fact that I can now ask a chatbot to produce almost any kind of text, and that by assigning words a numerical token and performing mathematical calculations, it can produce cogent essays, functional computer programs, and sorts of poems, seems to tell us something profound about ratiocination. It just might be computation all the way down. It’s in this equivalence that the interest lies, and the fear, and the wonder. What does the literary production of a machine tell us about what it means to be human? People want to know. That’s why so many articles get written, including this one.

But the fact of all of these articles, the endless churn of content about AI, might give us a different way in to thinking about what is after all not a philosophical argument, but a consumer product. The people making AI want to sell it, just as the people writing about it want to sell their takes about this question.

Rather than starting with the idea of the thinking machine, how might we think about text generation as the product that it is, ‘the fastest growing consumer product of all time’? Perhaps we can look, not to the early modern period, but to a later one. I mean the 19th century, or ‘the mechanical age’, as Thomas Carlyle called it, where ‘the great art of adapting means to ends’ strove to install efficiency as the world’s primary value. When we talk about the philosophy of mind, or the information nature of the universe, we might be missing the point. If we want to understand chatbots, we can skip the copernican revolution and head straight to the industrial one.

Carlyle’s point about the point about the logic of the machine is that it is inexorable. Literature, as a commodity contains, in principle, the idea powering Chat GPT. Marx, another 19th-century man, called it the rising organic composition of capital, but it might be easier to just say that any commodity, primarily made to be sold, is by definition going to make its owner better off being produced by a machine.

You don’t need Science Fiction or philosophy to dream of a machine mind. Good old realism will do. I was struck, for example, by this passage in George Gissing’s satire of the late 19th-century Literature industry, New Grub Street. Here, Marian Yule, one of the novel’s central characters, bemoans her role as an assistant to her father, a hack writer obliged to churn out endless book reviews:

She kept asking herself what was the use and purpose of such a life as she was condemned to lead. When already there was more good literature in the world than any mortal could cope with in his lifetime, here was she exhausting herself in the manufacture of printed stuff which no one even pretended to be more than a commodity for the day’s market. What unspeakable folly! To write—was not that the joy and the privilege of one who had an urgent message for the world?

Her father, she knew well, had no such message; he had abandoned all thought of original production, and only wrote about writing.

She herself would throw away her pen with joy but for the need of earning money. And all these people about her, what aim had they save to make new books out of those already existing, that yet newer books might in turn be made out of theirs? This huge library, growing into unwieldiness, threatening to become a trackless desert of print—how intolerably it weighed upon the spirit!

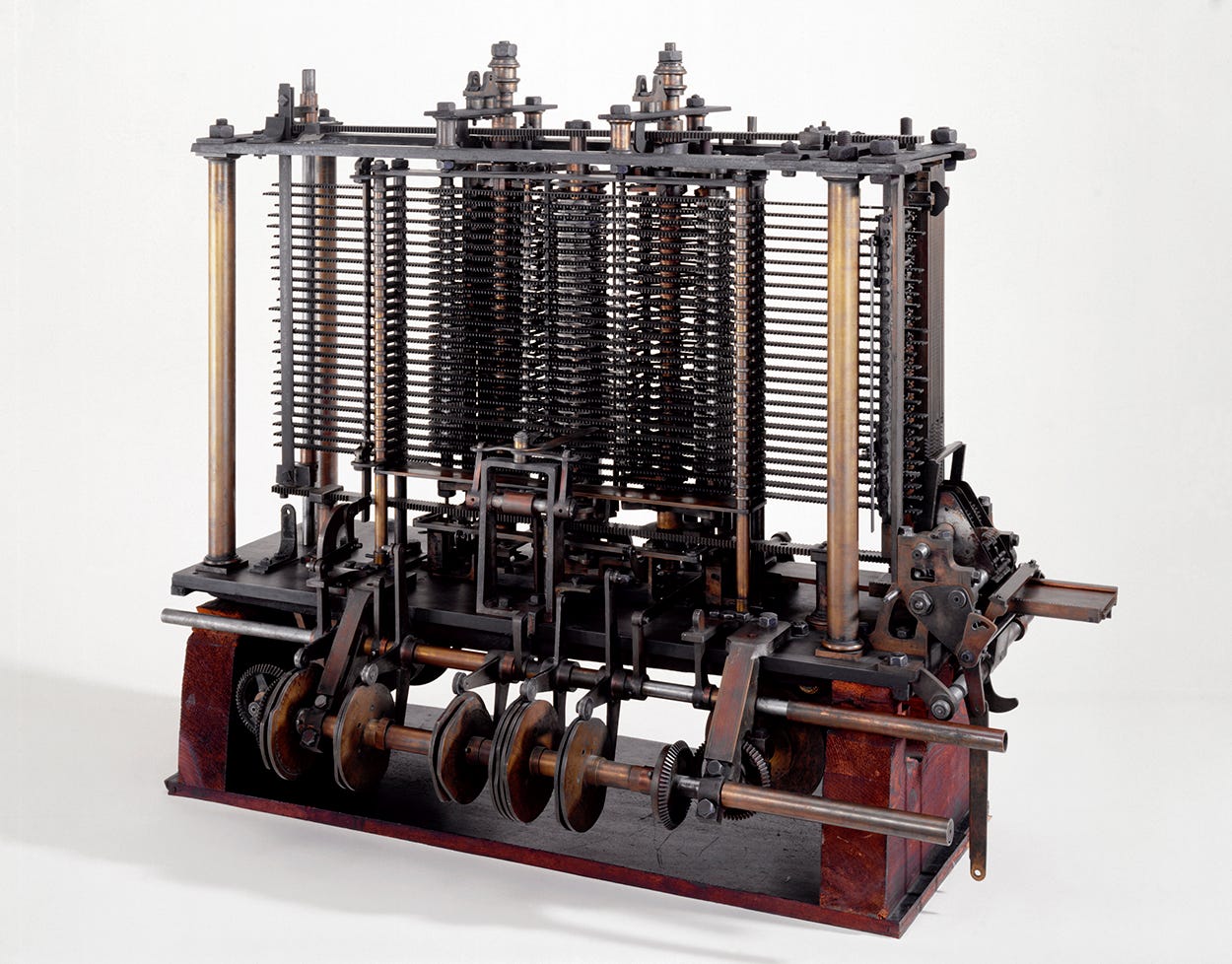

Oh, to go forth and labour with one’s hands, to do any poorest, commonest work of which the world had truly need! It was ignoble to sit here and support the paltry pretence of intellectual dignity. A few days ago her startled eye had caught an advertisement in the newspaper, headed ‘Literary Machine’; had it then been invented at last, some automaton to supply the place of such poor creatures as herself to turn out books and articles? Alas! the machine was only one for holding volumes conveniently, that the work of literary manufacture might be physically lightened. But surely before long some Edison would make the true automaton; the problem must be comparatively such a simple one. Only to throw in a given number of old books, and have them reduced, blended, modernised into a single one for to-day’s consumption.

Now, we are being told we do have the ‘literary machine’. In one way, the problem was comparatively simple. More and more training data seems to have done the trick. The books have all been blended and we have the endlessly personally customisable content production of ‘AI’.

Marian’s thought might not seem as profound as the question of the nature of the mind. But it goes deeper into why we’re being confronted with an AI revolution that even half the people doing claim not to want.

When discussing both AI and literature, I don’t think we have to start with the question of writing’s relationship to consciousness or consciousness’s to the universe. We should start with the labour of writing, as it exists and has existed historically, and the inexorable, algorithmic drive to save labour:

One of the arguments that AI boosters have been making is that Chat GPT will free up the world’s Marians; drudge writing will be a thing of the past. As someone who currently makes an almost living writing ephemeral articles, I’m less keen on this idea. The point, surely, is that drudge writing ought not to exist, not that it should be done for free and that I should become unemployed while the listicles continue to multiply and swarm around us, independent of any human’s desires.

I think the people who want to make claims about freedom from writing misunderstand what the freedom Marian seeks looks like, conflating several different kinds of labour or activity into one kind of value-producing labour, which can be optimised, and measured as time.

You cannot have the literary automaton without the idea of writing for money. It’s the only thing that makes it sensible. Or ought to. Most people would find the idea of having an AI converse with their friend on their behalf absurd. At least I hope they would.

The basic claim might sound silly to some people. Is it right to say there’s no one but a blockhead would use AI text generation for any reason other than money? Or failing that, saving time in money-determined contexts (writing school essays etc).

What about experimental artistic uses?—surely, like any other Oulipian constraint or whatnot, procedurally generated text can have a kind of artistic function? But that function, the function of the readymade, say, was always a way of trying to think about money. By erasing the labour of the artist, the readymade serves to raise questions about art, most people who’ve been to an art gallery know this. But the questions are intimately related to the money system anyway. They are asking where the value of art comes from.

But while this question in conceptual art was meant to subvert the ‘institution’ of art, it has collapsed now into a valorisation of the decision making power of the artist, of something like what cognitive scientists call executive function. We get rid of the grunt work and replace it with the conceptual labour of the Hollywood producer, say, who comes up with a ‘story idea’ for a film about robots that have feelings and rebel against their unfeeling human masters, and then hires some goons to actually write the words. The conceptual labour of the man who wants to make electric cars or fly into space, and so hires some scientists to do the actual labour. I said above that no one would have an AI converse with their friends, but executives have been getting their secretaries to reply to messages for years. People have a sense that they can simply have an idea—and someone else, or a machine, can embody it, when they don’t value the activity.

Conceptual art once seemed subversive by reducing art to this function. Arguably, it revealed that we didn’t live in a world that valued allegedly non-artistic labour as activity. A toilet is a beautiful pice of craftspersonship, even if made by an assembly line. A genius like Duchamp could help us see that, could help us see the value of all labour. But that idea failed, I think, in its aims and instead congealed into a vision of executive genius—see the total nullity of ‘conceptual poetry’ if you don’t believe me. It doesn’t subvert the institution of art but sells it short instead.

LLMs are the ultimate version of this in literature. I remember reading one of the many pieces of churnalism on the topic of AI writing wherein some tech dickhead was quoted saying something like “AI can’t replace the irreplaceable human element of creativity, but it can automate away the boring stuff, like descriptions”. I have yet to see a greater misunderstanding of writing as art, or a greater devaluation of human creativity than that. The man is doubtless correct about how this will go.

The idea that the material and the concept might modify each other, engage in a dialogue, in the act of writing—that description could be revelation, is alien to the mind of most people who are trying to produce machine writing. There’s a philosophical, and a political-economic-ideological underpinning for this. The philosophical is the general story of the machine mind—about the primacy of information over matter, of meaning and idea over thing. The idea is what matters, the story is reducible to its idea. The sentence to its proposition. But, I think the political economic is actually what matters when constructing the contemporary sense of creativity. What it means to be creative is precisely not to labour. Anything that can be thought of as labour can be automated. The true human essence in this fetishised idea of creativity is the idea, the vision of the entrepreneur, not the labourer that enacts it. Just in case you think it’s me saying this take a look at some guy, it doesn’t matter who, laying out his extremely scientific predictions for the future of AI:

What is the difference between a human and a worker?…

Some similar idea, you might think, is what Marian, in New Grub Street buys into. She serves her father’s purpose, though even his purpose his pretty pointless. You could read her as saying, like the man who wants to automate description, that what matters in writing is the idea, or ‘some urgent message for the world”.

But does some message need to be a proposition, an instruction, a prompt, like you would give a chatbot? Her vision is not of having a message and then telling someone else to write it, of being like her father, or a busy businessman—send my wife a card with some flowers—It is of having her labour and her intentions unified. That’s something else entirely.

*

By law, I think, one is obliged to use Chat GPT when writing about it, so here’s its summary of New Grub Street:

New Grub Street by George Gissing explores the challenges faced by writers in late 19th-century London. The novel revolves around the lives of two aspiring writers, Edwin Reardon and Jasper Milvain. Reardon, a talented but struggling novelist, faces poverty and the pressure to produce commercially viable work. Milvain, on the other hand, prioritizes success and marketability over artistic integrity. The novel delves into the themes of art versus commerce, the harsh realities of the publishing industry, the sacrifices artists make for their craft, and the clash between idealism and pragmatism in the pursuit of literary success.

It’s not how I would write it, but it’s ok. ‘Delves into the themes’ is an especially awful human touch. The LLM’s summary, though, doesn’t prioritise the novel’s romances, and Gissing’s weird obsessions with the intertwining of sex and class. It also, presumably because it associates the idea of a summary with a lot of blurbs and online reviews, doesn’t contain any spoilers.

Here’s another version. New Grub Street tells the story of the tangled careers and lives of two young, male writers, Jasper Milvain and Edwin Reardon, and the women they love, Marian and Amy Yule, as well as of the disappointments of Marian’s father, Alfred Yule. Reardon, who is trying to make it as a novelist cannot produce a decent commercial entertainment, and dies of the stress. In the end, the cynical Milvain, who mostly writes clever sounding articles, truly makes it by marrying Amy, Reardon’s widow, who has inherited a financial legacy, and abandoning Marian, whom it’s implied he loved more.

Now, what Gissing does really well in the book is, in a way, to use the romance plot, which is, by the by, the more conventional and therefore probably commercial aspect of the novel, to complicate its message about the degradation of art by commerce. What the novel lays bare, as ChatGPT points out, is the way money guides and shapes the literary production of the period. But what’s interesting is not this basic idea of the tension between art and commerce. Rather, the novel doesn’t allow its idea to become dominant.

You could see the parallels between love and art as an allegory. Milvain chooses the wrong woman, money over art, Reardon meanwhile is unable to satisfy his wife’s expensive tastes and therefore his art is destroyed by money. But the people in the novel don’t feel like these kinds of ciphers. No one is free of money worries, and no one is free of romantic or finer feeling. What matters, in the experience of reading the book is not that specific characters stand in for art, but that what we value in art is shown to be like what we value in a person. Art and love are both complex, both place in a web of human relationships. This web, of course, includes the vast abstract network of human relationships that is money, but though people do not escape the web, what we love about them, normally, is what seems to be distinctive, and not determined. Amy really does love Reardon. He is not some pure artist, either. No one is any one pure thing. No one is any kind of idea.

Because, I want to say, agreeing here with Thomas Hobbes, an idea can just be another kind of mechanism. A conclusion follows inevitably from a premise. That’s logic. That’s science. It’s also business. In most ideas, the goals one has mechanistically predetermine the means we use. The businessman who has great idea for a better chair, dreams not of the best chair, but of the optimal profit-making chair. The premise is profitability, the conclusion is the product. Capitalism itself, is of course, if not a machine, then an algorithm, a mathematical operation (profit, loss, M-C-M, however you want to construe it). As components of the machine this algorithm runs, we are forced to behave in certain ways according to its dictates. A lot of the people who seem to be leading the charge for AI say that we shouldn’t be doing it, but that they are forced to by the logic of competition. Even if, as I think is the case for many of them, they are exaggerating the dangers to get people talking about their product, they are still doing that because of the same logic. The creative vision of the ‘founder’, or the ‘writer’ who outsources their actual labour to Chat GPT can be just as mechanical as anything the LLM spits out. Everything is determined by the binary calculation of profit and loss.

Writing can do something else. A machine, in a certain sense, is the embodied labour of the dead who did not have that machine, of the people who dug the fuel to make it, etc. Words are something similar. Air worn into a certain useful shape by the vocal labour of millions. But words are the only machine that even slightly let you commune with the dead rather than use them. When we really work with them, we can imagine what it is like to be people, and not machines, not serving an abstract and implacably logical master.

The dream of actual AI, of a machine that becomes a person, is already a parody of what I think we long for in art. But being a person takes work.

A combination of work and life stuff, compounded by a near total absence of sleep, meant that newsletter pieces fell by the wayside recently. I hope to return to production at scale soon. There will be more content, including a rolling series on AI and aesthetics, of which this is the first, or a sort of teaser. I know that one of those will be a longer piece in response to Peli Grietzier’s essay on poetry as mathematical experience. You can also expect essays on a bunch of poets, on ‘Nietzsche, Philology, Christine Smallwood and Quitlit’, on Granta’s recent Best of Young British Novelists, and much more.

As I am, unfortunately, writing partly with the goal of competing in the attention economy, it would be great if you enjoy this, if you could share this post, tell your friends etc.